The early Internet: Joshua Cotter and Jesse Jarnow

Josh Cotter's 2016 Fantagraphics comic and Jesse Jarnow's reported book for Da Capo Press have me thinking about the marvels of Internet technology—both real and imagined.

Cotter's mystifying Nod Away can be traced to online origins, and it concerns the advent of an Internet that's, well, rather unconventionally networked.

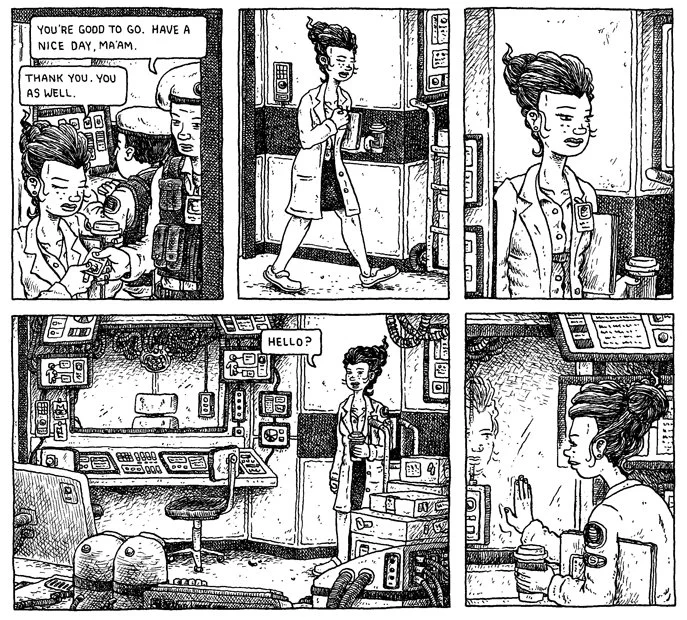

The Ignatz-nominated Cotter produced a couple of books for Ad House to wide critical acclaim, but his first for the Seattle publisher is an unnerving work of science fiction, the central story of which is rooted in the efforts to establish and maintain a universal cerebral "innernet," an Information Superhighway that exists in our heads rather than being supported by a massive computer network.

Having initially been published at Study Group in 2015, Cotter's Nod Away isn't easy to navigate and yields an open-ended final chapter, but it's only the first in a seven-book series that he had planned for four years before he started drawing.

As far as what's next, we'll likely hear more about Dr. Melody McCabe's work on the International Space Station "Integrity" as it relates to the ethical balancing act that requires both probing and nurturing Eva, the child who is powering Dr. Earnest's elaborate and volatile innernet, itself a seemingly brand-new and unregulated structure that's as sprawling and ripe for interpretation as Cotter's detailed work is.

A print-only side story in Nod Away is rife with open space, and has a bearded nomad hallucinating and wandering vast, hilly landscapes or pondering a big black night sky. Conversely, very little of the black and white pages in the main narrative—built of tightly composed panels—goes unoccupied. Cotter darkens each corridor with a net of dashes, while the tech that engulfs the facility's walls—frequently positioned behind his chatty scientists who turn to drugs, sex, or an iconic but mindless television series to stave off boredom—draws entirely on the analog control panels of vintage sci-fi films. There are glorious stacked decks with dials and screens and buttons and switches and worming ducts, each clashing with the more contemporary laptops and detailed tablet-type devices that appear elsewhere. The same level of fastidiousness goes for Cotter's Tumblr, where roughs of Nod Away, Volume II are going online.

They're loose blue-lead penciled pages and drafts—and are interspersed with a welcome look into his 2007-era sketchbook—but to me, it doesn't look like the finished second volume will land very far from the already intricate work we're seeing here.

In his new book Heads: A Biography of Psychedelic America, Jesse Jarnow writes briefly about West Coast underground comix publisher Last Gasp. Founded in 1970, Last Gasp was at one time home to books from Robert Crumb, Justin Green, and more, and the Heads author reports that one of its "partner(s) ... had formerly supervised a San Francisco acid lab." Jarnow, a friend of mine and established music journalist and WFMU DJ, mines in his book the history of psychedelic drugs, illuminates the broad, DayGlo-smeared strands of American counterculture's earliest days, and threads it all back to behemoth California rock band The Grateful Dead.

I get the sense that some of Joshua Cotter's weird pages and scrappy cartooning in Nod Away wouldn't look out of place in the sort of Last Gasp anthology that Jarnow might've highlighted in his book if he plunged any further down into that wormhole, particularly the sequence that features Cotter's hairy figure experiencing an out-of-body, psychoactive episode that materializes in a sensory deprivation tank.

But I wasn't so much thinking of Nod Away's art when I started Heads as I was its steadily smoking scientists and the parallels to Jarnow's focus on early Internet and computer technology, as pioneered by followers of the Dead.

"The Stanford Artificial Intelligence Lab in late 1972 is just as much a product of Palo Alto as the Grateful Dead or Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters," writes Jarnow amid a blitz of not-insignificant names, show dates, and accounts of peyote sales that we're supposed to keep straight in Heads. "And like Kesey and Robert Hunter's LSD use at local government VA hospitals, there is a complex mix of forces and funding at work at the inception of what will be a prolonged revolution."

Jarnow unpacks the roots of SAIL, one of the few scientific facilities that produced most of the research and computer equipment that led to the development of the Internet.

At its terminals, loads of Dead advocates—both dedicated heads and casual hangers-on—toiled daily and nightly on numerous experiments, one of which included the programming of the first-ever video game, "a flawless crystal ball of things to come in computer science and computer use," according to Rolling Stone's Stewart Brand in 1972 (Merry Prankster Brand is a well-known counterculture icon whose contributions are detailed heavily here).

Brand's flashy account of "Spacewar" is cited in Heads, but via humorous eyewitness anecdotes and grounded reporting that proves riveting even if your knowledge of Garcia & Co.'s work doesn't extend much farther than "Dire Wolf" or American Beauty's nimbly woven pearls, Jarnow goes deep.

With regard to Silicon Valley, the author paints a much larger picture than the one he mapped out for a pre-Heads piece in WIRED last year—we get the skinny on pot plants that were grown around SAIL's septic tank area and a primitive electronic mail system that coders used to alert each other of Dead shows, potential transportation options to war protests, and collaborative smoking sessions.

We also learn that SAIL is where the first-ever "status update" happens, along with early e-commerce in communication that supported an inter-lab weed sale between Stanford and MIT. But for both the uninitiated and those in the know, by the time Jarnow gets to this part of America's winding relationship with psychedelics, we're still at square one. Much like the baked programmers probing for bugs in the world's first video game at the Stanford Lab in 1972, Heads has only just begun, and there are hundreds of pages of a carefully reported "prolonged revolution" ahead.

Nod Away images © 2015 Joshua W. Cotter. Heads: A Biography of Psychedelic America cover © 2016 Da Capo Press. Additional art by Victor Moscoso in “LUNA TOON," Zap no. 2, 1968.