Meags Fitzgerald's 'Photobooth: A Biography'

May 12, 2014—After ten or so years of exploring and experimenting with automated photography, Canadian writer and illustrator Meags Fitzgerald found herself crowd-funding travel and reporting expenses in 2012 for what would become Photobooth: A Biography, a nonfiction graphic work that's one-half diary comics-styled storytelling and one-half comprehensive history of vintage photo booths.

Fitzgerald can't help it—she's long been enamored of photo booths, specifically of chemical photo booths. In her debut book's prologue, amid a fluid array of explanatory copy, mechanical drawings, and diagrams, each defined in rigid black lines and grayed-out in swathes of charcoal, chemical photo booths are carefully dissected.

Fitzgerald looks fondly back at high school in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada when she deemed herself "the photo booth girl." A meaty discussion follows in Photobooth of how the chemical/wet chemistry booth works, as opposed to digital photo booths, the production of which "has drastically altered the chemical photo booth industry."

Fitzgerald's book is a dense study (and probably not ideal for those uninterested in the subject), but there's a balance to her work—the sort of formal examination of photo booths that we might find in a college textbook is bolstered by deep anecdotes and observations, while the reasoning as to why she'd do this (why comics, why photo booths) is honest and smart.

"By researching the past and by piecing together my own memories," she writes, "I've tried to construct portraits, sometimes to celebrate and other times to commemorate, the ultimate portrait-making machines."

In Part I, that commemoration is pinned to a timeline that connects Fitzgerald's subject matter to the birth of automatic photography machines in 1839, as there are "approximately seven predecessors" to the modern photo booth. Detail-rich drawings of early photography devices appear alongside contextual patches of copy, each set off by the date at the center of the discussion.

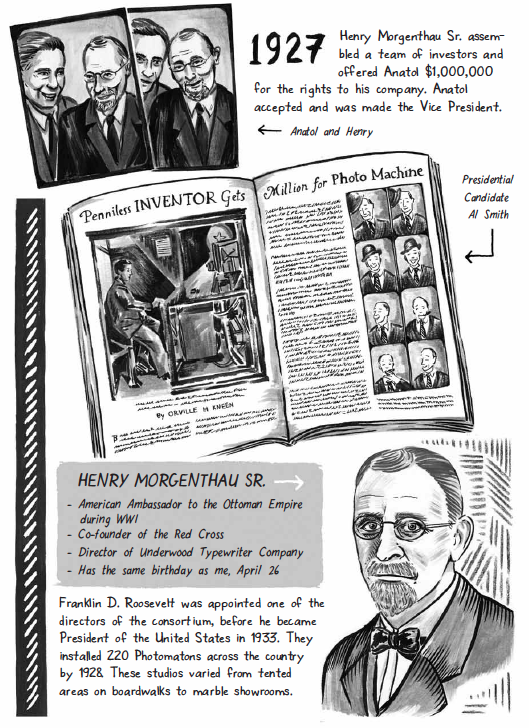

Fitzgerald's illustrative style shifts sporadically throughout the book, which lends a likely intentional sketch diary aesthetic to her work (she cited a similarly plotted Carnet de Voyage from creator Craig Thompson as an influence in a chat with Cult Montreal writer Kayla Marie Hillier). There are technical drawing chops on display in Photobooth for sure, but in Part I, polished portraiture is blended with a fascinating handful of renderings of Siberian photographer/technician Anatol Josephowitz that mirror the careful chisel work required of woodcut. Also supportive of the "diary" look here is that the narrative text in Photobooth is never boxed-off. Fitzgerald instead builds out white spaces against the soft grey strokes that define the book's occasional newsprint-like backdrop.

An abbreviated version of Anatol Josephowitz's place in the history of automatic photography might be known to some—he debuted the first photo booth in New York City in 1925, which dealt eight photos per strip in eight minutes. After having drawn "crowds up to 7,500 per day," wrote the Toronto Star's Ryan Bigge in 2008, Josephowitz sold the patent rights to his machine for a sizable sum and the "Photomaton soon spread across America."

Capped by a lovely full-page portrait of the first Photomaton ("fourteen years in the making"), with her venturesome linework tracing the swirl of the wood grain of the booth's panels and the floor beneath it, Fitzgerald's chronicling of Josephowitz's contributions are integral to Photobooth's subject matter. Her telling of his actually quite complicated role is clever and specific. Newspaper clippings and passports litter the pair of pages that detail Josephowitz's early years, and Fitzgerald directs her attention to the varied geography that dots his backstory, producing evocative charcoal drawings of hilly Manchuria, a Manhattan skyline, and Shanghai, where a cluster of hanging street banners dangles overtop a busy street scene.

When Fitzgerald connects her enthusiasm for photo booths to her comic's rigorously reported background—she spoke with collectors, technicians, photobooth owners, and more to establish a thorough history—she traces her interest to the early 2000s, when she found photo booth pictures of her mother from when she was in her twenties. From there, Fitzgerald describes a rhythmic "adrenaline rush" that she equates with the experience of being in a photo booth. "Taking pictures became a personal ritual" for her as a teen, which opened her world up to performing improv, making experimental art, and more.

Framed frequently in drawn strips of photo booth pictures (each rooted in Fitzgerald's collection) or illustrated photos of the author and her friends, Photobooth's intimate memoir pages are interspersed with loads of contextual material. Anatol Josephowitz's story and that of the photo booth continues, and so does Meags Fitzgerald's.

Renderings of photo booths over the years are given splash page treatment, and the creator maintains the book's loose visual structure throughout, as informative text gets paired with staggered drawings of vintage ads, portraits of major and minor players in the machine's history, and precise mechanical illustrations of technical improvements that have been made over time.

Stories from Fitzgerald's varied sources are documented with narrative flair, and while the subject matter so often calls for a straightforward, realist approach on the visual end, sometimes a whole page is overrun with clever design. There are florid patterned borders, magazine-style pull quotes from the artist's interviews, and even striking psychedelic flourishes.

In Photobooth, it's as if we get a thorough history lesson from one of those teachers who can do nothing to stem her obvious affinity for the material. And as expected, the experience is better for it.

All images © 2014 Meags W. Fitzgerald. Buy the book at Etsy.