Clickable

NOAH VAN SCIVER IS IN THE WOODS

For an all-comics issue of Toronto-based literary magazine Taddle Creek in the winter of 2015, award-winning cartoonist Noah Van Sciver submitted a candid three-page autobiographical story he called "Home." In the full-color comic, Van Sciver reveals that a relationship of his went abruptly south after a woman he'd been dating called it off, which sent him in search of new digs. "This past year I've lived in 3 different apartments," says a seated Van Sciver, head-on to the reader, in the first of three panels.

Muted soil browns and earthy green tones within an overall dark-hued palette set a somber scene but give way to a humorous entry from the artist -- he recounts a time in Denver, where he secured what I assume were small paychecks at an alt-weekly and commissions -- and the road that led him to a fellowship at Vermont's Center for Cartoon Studies.

The last large panel has Van Sciver again speaking directly to us: He's in a patch of New England woods, amid lots of yellow and autumnal reds discussing the plan to "keep working hard and pushing forward." The mood has shifted considerably, and the colors are much brighter than those he uses for the first page here.

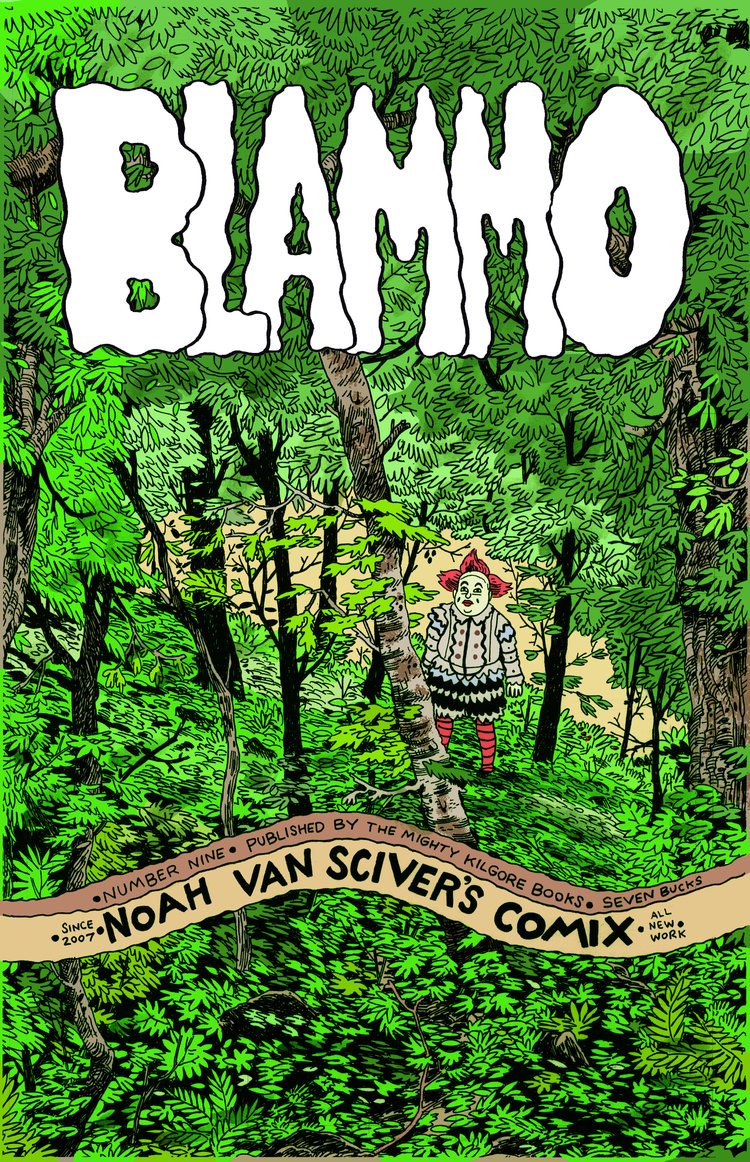

There is a return to the solace of the forest in the ninth and newest issue of Blammo, a long-running comics anthology series from Kilgore Books that features a combination of memoir comics and fictional pieces, all produced by Van Sciver.

The work here is affecting and often funny when humor is unexpected, particularly in an autobio account of Van Sciver's interactions and self-examination at CCS. He plots the six-by-nine inch black and white pages of "White River Junction, Vermont" in Blammo #9 with twelve square panels that are crowded with frank and frequently laugh-out-loud exchanges between the cartoonist and other artists who ostracize him for having admitted to a Mormon upbringing.

Van Sciver, whose mouth in these pages is perpetually tucked behind a drooping, bushy mustache, is soon slumped in a chair across from a campus counselor, defending himself against "drama" and apparent gossips who've deemed him a bully. He reflects on his past and conjures images of his childhood to battle broadening frustration that threatens to derail the work in his studio.

As he had in the Taddle Creek comic, the last couple of pages of the story find the cartoonist withdrawing to the woods. He carries a sketchbook and looks to the higher power that played a role in his on-campus quarrels.

"Let me know you now," says Van Sciver, looking upward into the trees and an exquisitely detailed tapestry of pine needles and stately maple trees. It's a beautiful sequence, and you can almost hear the patter of rustling leaves.

FIFTY-YEAR-OLD RECORDS

In March of 1967, Verve Records issued The Velvet Underground & Nico, an erratic, lo-fi affair that owes to messy fuzzbox guitar leads, curt, amplified viola lines, and which featured Andy Warhol's now iconic "banana" print on its cover. VU was a New York City avant-garde four-piece rock band in 1967, but they'd been featuring Cologne, Germany-born actress, model, and singer Nico at their performances, and she led three of the songs on the debut.

The album runs from serene ("Sunday Morning"), to blues-charged ("I'm Waiting For the Man"), and in the instance of "All Tomorrow's Parties," gauzy and lush, but somewhat lean-sounding, its lyrics a dispatch from Warhol's 47th street studio/live art space.

"(Lou Reed) got maximum mileage from his role as an objective observer at the Factory, where he would take longhand notes on overheard conversations, behavioral quirks and the interaction of the habitués of Warhol's world," writes Joe Harvard in his 33 1/3 book on the album.

"All Tomorrow's Parties" is a mournful march with manipulated piano and fraying tones from guitarist Lou Reed, who tuned each of his strings to D for this rather singular trip for American rock, especially in a year that would produce scores of hyper-polished, Beatles-aping artifice tailored solely for radio charts.

The recorded version of “All Tomorrow’s Parties” appears to be a far cry from what were at one point similarly grounded ambitions. Speedy acoustic guitars underpin 1965-era demos, with pre-Nico vocal harmonies rendering the tune a snug albeit icy fit for smoky Greenwich Village coffeehouses of the era. The take that landed on the record is nowhere near as quaint -- it's a moving, rich piece of art rock that still plays as fresh, decades down the line.

MAGAZINES AND MOVIES

If I’d actually gotten around to a “favorite longform writing” post as I’d done last year, Ta-Nehisi Coates’s reported essay for The Atlantic on Obama’s presidency would’ve had a slot. I read it over the holidays, and it was worth it:

When President Obama and I had this conversation, the target he was aiming to reach seemed to me to be many generations away, and now—as President-Elect Trump prepares for office—seems even many more generations off.

Obama’s accomplishments were real: a $1 billion settlement on behalf of black farmers, a Justice Department that exposed Ferguson’s municipal plunder, the increased availability of Pell Grants (and their availability to some prisoners), and the slashing of the crack/cocaine disparity in sentencing guidelines, to name just a few. Obama was also the first sitting president to visit a federal prison. There was a feeling that he’d erected a foundation upon which further progressive policy could be built. It’s tempting to say that foundation is now endangered. The truth is, it was never safe.

We went to see Purple Noon — a French 1960 film adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley — on 35mm film at Metrograph last weekend. It was filmed all over gorgeous coastal Naples and elsewhere in Italy, and I was glad to be watching those florid colors and frequently unnerving sequences on the big screen, even if director René Clément's shifts from the excellent book include preventing Highsmith's devious sociopath from getting away with murder.

Although I don't remember the book's homoerotic subtext being very prominent in the 1960 onscreen adaptation of The Talented Mr. Ripley, writer Wendy Lesser finds that it's magnified at least once in an insightful piece on the story and Clément's film:

Still, even as he pursues this pseudo-romantic, victimized-murderer line, Clément retains his grasp on one of the novel’s basic elements: wishful identification merging into homo-eroticism. The scenes between Delon and Ronet, often in alternating close-up, emphasize the ways in which these actors resemble each other. And even when the two men are at their most antagonistic—discussing aloud why Ripley might want to kill Greenleaf, for instance—they are collusive and intimate, purposely keeping their conversation hidden from Marge.

John Seabrook’s New Yorker essay about drinking is rich with carefully built passages that are funny, intimate, and at times deeply gutting:

Many of the red wines were older than I was. It pleased my father greatly that the year of my birth, 1959, and that of Bruce, my brother, 1961, were shaping up to be first-rate vintages, in both Burgundies and clarets. Later, after the wines had further matured and become famous vintages—wines that Gordon Gekko might have sent Bud Fox as thanks for an insider tip in “Wall Street”—they featured prominently in our early-adult milestones, homecomings, and victories. My father opened a lesser 1959 Bordeaux on my twelfth birthday and proposed a toast in which he compared me favorably to the wine. I would always be measured against my birth wine; the wines kept getting better.

Images from "Home" © 2015 Noah Van Sciver. Images from Blammo #9 © 2016 Noah Van Sciver for Kilgore Books.