Infected by the cold of the graves

A new volume from Fantagraphics Books debuts in English the complete run of horror/science fiction comic Mort Cinder, a dramatic black and white Argentine strip that sees graying antiquarian Ezra Winston — as a result of handling the oddities carted into his London shop — tangle with supernatural, often chilling episodes that involve a resurrected dead man.

The new book is the first in a series from the Seattle publisher that will celebrate Uruguay-born artist Alberto Breccia, who told Spanish comics magazine Zeppelin in the 1970s that his wife was dying while he worked on Mort Cinder alongside writer Héctor Germán Oesterheld.

Breccia's weekly paycheck couldn’t cover the cost of her daily prescriptions, and the artist subsequently left the medium to teach art for a short period. His gold-etched name gets top billing on the new collection, and in the afterword, scholar Janis Breckenridge writes about the strip's significance as a relic of the “Golden Age of Argentine Comics”:

At first glance, it might seem that Mort Cinder's plot structure is relatively straightforward if not downright simplistic. Over and over again, objects Ezra and Mort encounter in the antique shop evoke the past, prompt a story or, at times, lead to direct intervention in historical events. But it is this very framework that made it possible for the artist, Alberto Breccia, and the writer, Héctor Germán Oesterheld, to not just employ but to exceed the parameters of traditional adventure comic strips and serials.

Héctor Oesterheld scripted comics for a number of publications and had already worked with Breccia before Mort Cinder's inception — as well as with revered Italian artist Hugo Pratt — on action and adventure strips such as Ernie Pike, Doctor Morgue, and Sherlock Time. So by the time of Mort Cinder's publication in weekly Mexican magazine Misterix in the summer of 1962, the writer's place as a leader in the history of Argentine comics had been forged in his best-known work — 1957's wildly successful serial science fiction strip about suburban Argentines battling a violent alien invasion called El Eternauta (“The Eternaut”), which was drawn by Francisco Solano López and launched in weekly magazine Hora Cero.

Breccia helmed art duties on a more overtly political El Eternauta relaunch in 1969, which followed his collaborations with Oesterheld on the 1950s comics, a graphic biography of Ernesto “Che” Guevara, and Mort Cinder.

As I wrote for Hyperallergic in 2016, the political overtones in works like El Eternauta and Che were likely what drew the attention of the Argentine dictatorship toward Oesterheld: He and several family members disappeared in the late 1970s, when he was kidnapped by militarized forces dispatched by the government and never seen again.

Death enshrouds the ten stories written for Mort Cinder, a comic thematically fixated on impermanence that ended after only two years and ran infrequently in the magazine where it was first published. Breckenridge notes that its "very name (death, ash) suggests cycles of dying and rebirth" — the strip is heavy with this finality from its first post-prologue appearance ("Lead Eyes"): Winston's trade is in preserving and cataloging art and objects of past lifetimes and of people long gone.

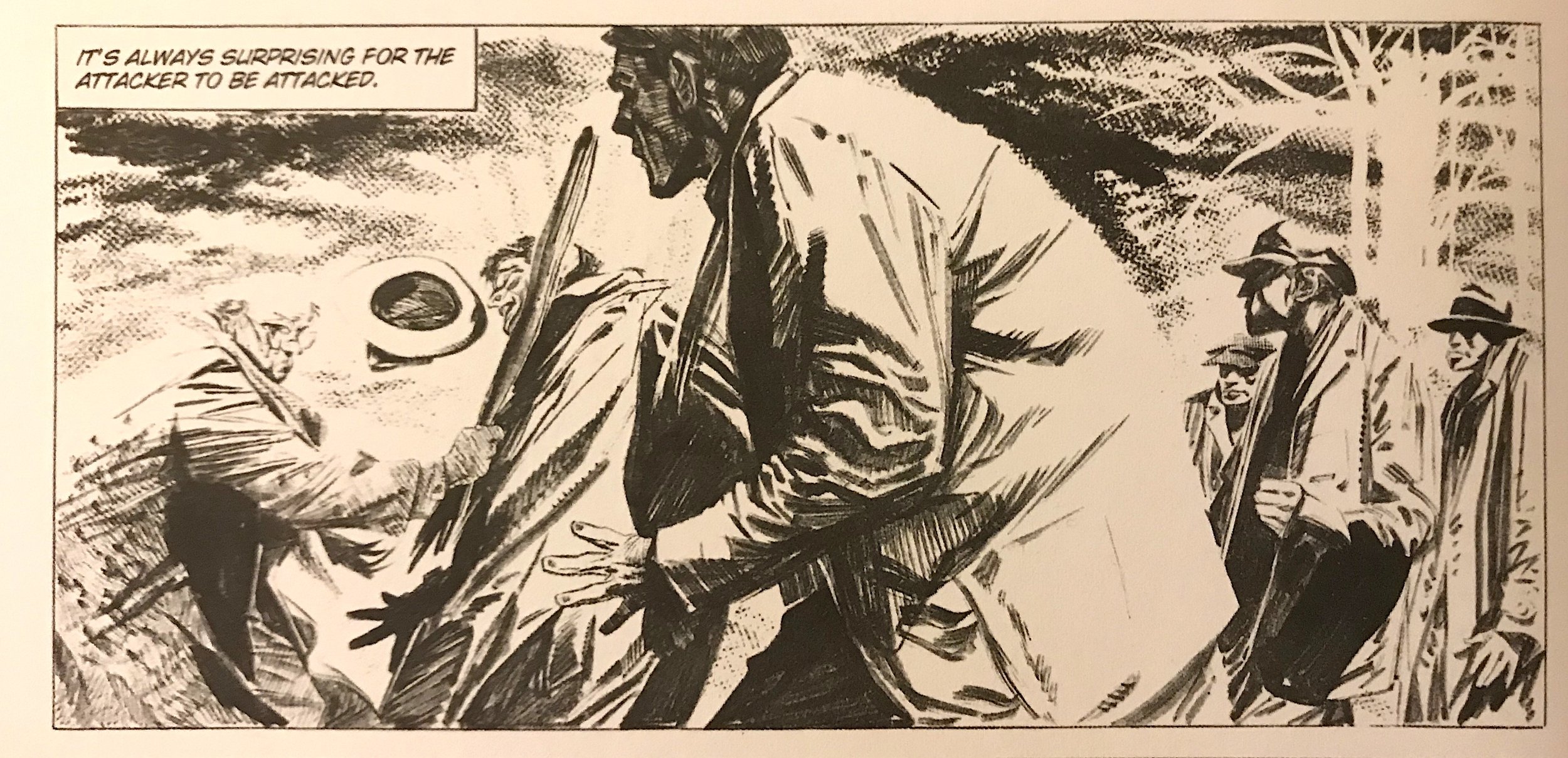

The messenger who introduces the main story, which revolves around a walking dead man, delivers an artifact that is pivotal to the subsequent installments — wrapped in newspaper with the headline "Murderer Mort Cinder hanged this morning" — is first described as "skeletal" and, ultimately, a "skeleton." Oesterheld and Breccia's antiquarian literally climbs into an open grave in the fourth strip, when Winston is pursued by ghoulish, gangly "leaden-eyed men" cloaked in thick black shadows. The language itself throughout Mort Cinder, which is rife with historical allusions, is suffused with death and gothic imagery:

"I plunged into the underground..."

"I felt cold...as though infected by the cold of the graves."

"His shoes...sounded too much like something viscous coming off a tombstone."

Vivid lyrical imagery aside, having worked through some of this big book, I find myself agreeing with what critic Matt Seneca gets at in The Comics Journal, that these strips are "variable in quality," narrative-wise. The effect that the visuals have on me, however, is altogether different.

Breccia, whose innovative, mixed-media visualizations of H.P. Lovecraft stories would follow Mort Cinder a decade later, used toothbrushes, razors, and more to produce textured finishes and harsh, bottomless blacks in his fastidious drawings. Breckenridge cites his working in "a completely dark studio space lit only by candles."

In these early chapters, Breccia's ink-spattered cemetery backdrops and damp, winding English nooks, lined with ornate housing facades and shadowy cobbled streets partner with a stylish representation of what's commonplace in the strip—the ubiquitous skin folds in Winston's face (modeled after the artist's own), his furrowed brow, the flecked pattern on his scarf and overcoat.

A six-page "Prologue: Ezra Winston, Antiquarian in 'The Gift of the Pharaoh,'" which isn't connected to the "Mort Cinder" character and never even leaves the confines of Winston's store, is replete with magnificent composition. Note the pristine lines in Winston's furnishings and stray artifacts in the establishing panels. Or the illustrative detail in the Egyptian woman's geometrically elaborate garb. Or the marvelously realized, proto-psychedelic orbit of blots and inky swirls in the shopkeeper's hallucination. The culminating effect is striking—Breccia's ashen pages leave me transfixed, as if I were handling some rare and precious object for the first time.